Tinker Hatfield: Architect of Air and Innovation at Nike

Tinker Hatfield is more than just a shoe designer – he’s a legend in the sneaker world, revered for turning athletic footwear into cultural icons. Often called the “mad scientist” behind Nike’s most groundbreaking shoes, Hatfield has been credited with saving Nike from slumps not once but twice through his visionary designssneakerfreaker.com. From inventing the visible Air unit to redefining Michael Jordan’s signature sneakers, Hatfield’s work seamlessly fuses function, storytelling, and style. This extensive look at Tinker Hatfield’s life and career explores how a former athlete-turned-architect became the driving force behind many of Nike’s most famous designs. We’ll dive into his early life and influences, his transition from architecture to sneaker design, and the inspirations and design choices that have made his creations legendary among sneakerheads and athletes alike.

Early Life and Athletic Beginnings

Tinker Linn Hatfield Jr. was born on April 30, 1952, and grew up in Oregon. From a young age, he was immersed in sports – at Central Linn High School he excelled in basketball, football, and track & field, earning All-State honors in football and All-American status in hurdles and pole vaultdesign.uoregon.edu. In fact, in 1970 Hatfield was named Oregon’s top high school athlete of the yeardesign.uoregon.edu, a testament to his all-around athletic prowess. This competitive sports background would later inform his approach to design, giving him firsthand insight into athletes’ needs. Hatfield’s unique nickname “Tinker” actually came from his father: as Hatfield recounted, his dad was nicknamed Tinker after being placed in a Tinker Toys box as a premature baby, and the name was passed on to Tinker as the firstborn sonsandpointonline.com. That quirky moniker would become famous in its own right as Tinker Hatfield rose to prominence at Nike.

After high school, Hatfield attended the University of Oregon on a track and field scholarship. There he trained under legendary coach Bill Bowerman – who happened to be the co-founder of Nike – and studied architecture as his majoren.wikipedia.org. Hatfield was a star pole vaulter for the Oregon Ducks, even setting the university’s pole vault record and placing sixth in the U.S. Olympic trials in 1976design.uoregon.edu. However, a devastating ankle injury during his college years cut short any Olympic dreamsblog.laced.com. Hatfield underwent multiple surgeries and two years of rehab for the injuryblog.laced.com, forcing him to shift his focus from athletics to academics. In 1977 he earned his Bachelor of Architecture degreeen.wikipedia.org. Though initially a setback, this dual experience in elite sports and architecture would prove to be a powerful combination in Hatfield’s design career. Bowerman, known for his tinkering with running shoes, had instilled in Hatfield a problem-solving mindset: the idea that designing footwear was fundamentally about solving athletes’ problems. Hatfield later noted that Bowerman’s philosophy influenced him greatly, recalling Bowerman’s advice that “No matter what anyone tells you, you have to think for yourself”blog.laced.com. Little did Hatfield know he would soon carry that lesson into a role that merged his athletic insight with his architectural creativity.

From Architecture to Nike Footwear Design

Armed with his architecture degree, Hatfield initially worked as an architect in Eugene, Oregon for a few yearsen.wikipedia.org. In 1981, he joined Nike – not as a shoe designer, but as the company’s corporate architectsandpointonline.com. His first job at Nike involved designing buildings: offices, showrooms, and retail spaces on the Nike campus in Beavertonsandpointonline.com. Hatfield was essentially Nike’s in-house architect, applying his design training to the company’s physical infrastructure. By this time Nike was growing rapidly from its Blue Ribbon Sports origins, and the young architect Hatfield was helping shape its campus. Yet he maintained a close connection to sports and athletes, even working out at the local YMCA and observing the athletic culture around him.

Hatfield’s transition into footwear design came a few years later, almost by serendipity and personal initiative. In 1985, he began to experiment with shoe design, realizing that his architectural skills – sketching, structural concepting, creative problem-solving – could be applied to athletic shoesen.wikipedia.org. Nike’s management was opening up opportunities for cross-disciplinary innovation, and Hatfield seized the moment. He officially switched over to Nike’s product design group in 1985design.uoregon.edu. That career pivot would launch an era of unprecedented creativity in Nike’s design labs. By 1989, Hatfield had become Nike’s Creative Director of Product Designdesign.uoregon.edu, a rapid rise reflecting the impact of his early footwear concepts.

One oft-cited anecdote from Hatfield’s early design days is how he essentially invented the “cross-trainer” shoe – a new category of athletic footwear. The idea was born from simple observation: Hatfield noticed that people at his Portland gym were either carrying multiple pairs of sport-specific shoes or, worse, wearing one pair of shoes for all activities (like running in basketball shoes) and getting subpar performancenickdepaula.comsneakerfreaker.com. Drawing on his own experience as an athlete, Hatfield saw an opportunity. “I didn’t want to have to pack around two or three shoes, and I didn’t want to wear one pair that was really inadequate,” he said of his epiphanynickdepaula.com. He sketched a shoe that could handle a bit of everything – running, basketball, weightlifting, aerobics – good enough for a diversified workout at the Y. This concept became the Nike Air Trainer 1 in 1987, the first multi-purpose cross-training sneakersneakerfreaker.com. It featured a mid-height cut for lateral stability, a forefoot strap for support, and a versatile design that could transition from the track to the courtsneakerfreaker.com. The Air Trainer 1 was a hit, boosted by clever marketing that had tennis bad-boy John McEnroe and two-sport star Bo Jackson as its championssneakerfreaker.com. More importantly, it exemplified Hatfield’s approach of solving an athlete’s problem through design – in this case, simplifying life for the multi-sport enthusiast. Nike’s faith in this unorthodox idea paid off hugely, as the cross-trainer opened an entire new segment of the market and helped re-establish Nike as an industry leader by the late 1980snickdepaula.comnickdepaula.com.

Tinker Hatfield drawing in studio. Hatfield’s background in architecture gives him a unique perspective on form and structure, even when designing something as small as a sneaker. He often surrounds himself with prototypes and inspiration boards in Nike’s Innovation Kitchen (design lab) as he refines each concept.

Another revolutionary early project of Hatfield’s was the Nike Air Max 1, which introduced the world to visible Air cushioning. In the mid-1980s, Nike’s Air technology (gas-filled cushioning in the sole) was still relatively new, hidden inside the foam of running shoes like the Tailwind. Hatfield thought like an architect and literally turned the shoe “inside-out” to expose its structure. He took inspiration from an unlikely source: the Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris – a high-tech building famous for displaying its pipes, ducts and structural elements on the exterior. After visiting the Pompidou, Hatfield was struck by the idea that the Air unit inside a shoe could be made visible by cutting away part of the midsoleblog.laced.comsneakerfreaker.com. This design was bold and unprecedented – so much so that some Nike colleagues thought the exposed Air window looked structurally unsound and nearly “cost him his job” for being too radicalblog.laced.com. But Hatfield persisted with confidence in the concept and his aesthetic vision. The Nike Air Max 1 debuted in 1987 with its clear Air bubble visible on the side of the sole, and it was an instant icon. The shoe’s success validated Hatfield’s risk-taking. It proved that showcasing the technology could be both visually striking and commercially successful. That visible Air unit, once controversial, became a hallmark of Nike design and a feature that countless sneakers have adopted sinceblog.laced.com. Hatfield later reflected on this breakthrough: “The Air Max 1 was so bold for its time that it almost got me fired. Thankfully, it saw the light of day, as it is still one of the most influential sneakers in the modern market”sneakerfreaker.com. Indeed, the Air Max line would go on to be a cornerstone of Nike’s lineup, and it all started with Hatfield’s architectural problem-solving approach to sneaker design.

The Michael Jordan Era: Saving the Air Jordan and a Legendary Partnership

While Tinker Hatfield had already flexed his design muscles on running and training shoes, his most famous contributions would come on the basketball court – specifically through his partnership with Michael Jordan. By the late 1980s, Michael Jordan was a rising NBA superstar with two Nike signature shoes (the Air Jordan 1 and 2) under his belt. But behind the scenes, all was not well: Jordan was reportedly unhappy with the Air Jordan 2 and was seriously considering leaving Nike for Adidas around 1987sneakerfreaker.com. Around that same time, the original Air Jordan designers (Peter Moore and Bruce Kilgore) had left Nike, leaving the future of the Jordan line in limboblog.laced.com. Nike’s management knew they needed something special to keep Jordan from jumping ship. The task of designing the Air Jordan III (3) – and impressing Michael Jordan himself – fell to Tinker Hatfield in a fast-turnaround situationblog.laced.com.

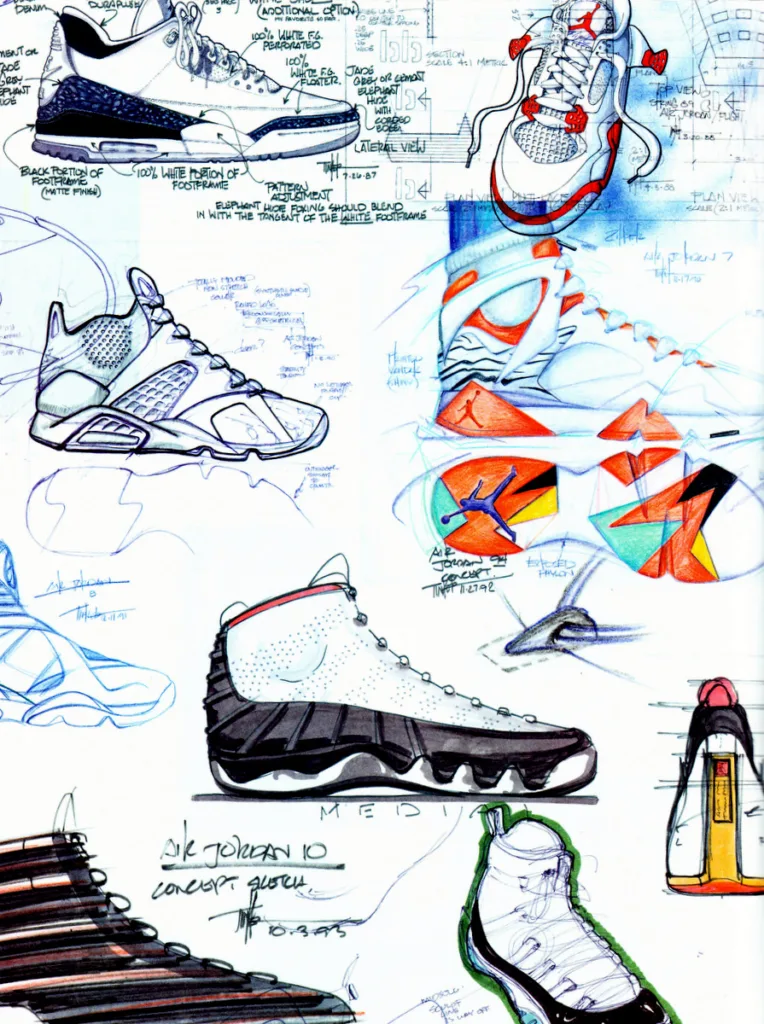

Hatfield approached the Air Jordan 3 project the same way he’d approach an athlete’s problem: by listening and innovating. He famously met with Michael Jordan to hear what the superstar wanted in his next shoesneakerfreaker.com. Jordan’s requests were clear: he wanted a mid-cut basketball shoe (something between a high-top and a low-top, which was unusual at the time), a shoe that felt broken-in right out of the box, and he wanted a distinctive new style – including a pattern or material that hadn’t been seen before on a sneakersneakerfreaker.com. With this feedback, Hatfield went to work. The result was the Air Jordan III, released in 1988, which featured a slew of innovations tailored to Jordan’s desires. It was the first mid-cut basketball sneaker, offering both ankle support and flexibilitysneakerfreaker.com. Hatfield picked a soft, tumbled leather for the upper so that the shoe would be comfortable from day one yet still supportivesneakerfreaker.com. And for a striking visual element, he created the now-famous “elephant print” overlays on the toe and heel – a textured grey/black print unlike anything on basketball shoes beforesneakerfreaker.com. This bold pattern satisfied Jordan’s urge for something different and iconic. Notably, the Air Jordan 3 was also the first Jordan shoe to prominently feature the Jumpman logo (the silhouette of Jordan leaping) instead of the Nike Swoosh – a design choice Hatfield made to help build Michael’s personal brand on the shoeblog.laced.com. The Air Jordan III was a masterpiece in merging performance and style: its visible Air sole (borrowed from Hatfield’s Air Max concept) gave it tech credibility, while its luxury details (like a faux-luxury elephant print and a sleek mid-cut profile) made it fashionable off the courtblog.laced.com.

Crucially, the Air Jordan 3 absolutely wowed Michael Jordan. It not only convinced him to stay with Nike, but it arguably cemented the future of the entire Jordan Brand. In Michael’s own words after seeing Tinker’s work, “Tinker has always been great at delivering for me” – and the sales spoke volumes. The AJ3 helped Nike make $162 million in Air Jordan sales in that first year alonesneakerfreaker.com. Phil Knight later praised Hatfield’s pivotal role, crediting him as the “savior of Nike” for rescuing the Jordan franchise and, by extension, keeping Nike at the forefront of the industrysneakerfreaker.com. By solving Jordan’s concerns with innovative design, Hatfield didn’t just design a hit shoe – he nurtured a partnership with Michael Jordan that would span decades and yield many of the most beloved sneakers in history.

Over the next several years, Tinker Hatfield and Michael Jordan formed a legendary designer-athlete duo. Hatfield went on to design Air Jordans III through XV (3 through 15) in continuous collaboration with MJen.wikipedia.org, as well as later models like the 20, XX3, XXV (2010), and XX9en.wikipedia.org. Each year’s model pushed new boundaries in technology and style, often drawing from some aspect of Jordan’s life or persona. Hatfield’s design choices and inspirations for the Air Jordan line became the stuff of sneaker lore. For example, the Air Jordan V (1990) sported jagged “flames” on the midsole – Hatfield took inspiration from the nose art of World War II fighter planes, thinking it suited Jordan’s aggressive, high-flying playing stylegq.comsneakerfreaker.com. He even tweaked the motif: traditionally flames on aircraft are painted trailing backward, but Hatfield pointed them forward on the Jordan V to symbolize always moving aheadgq.com. The Air Jordan VI (1991), in which Jordan won his first NBA championship, had a heel tab that was inspired by the rear spoiler of Michael’s sports car, adding a sleek automotive vibe to the shoe. When designing the Air Jordan XI (1995) – which many fans consider one of the greatest Jordans – Hatfield broke with convention by adding glossy patent leather to a basketball shoe. This was partly a functional decision (the patent leather doesn’t stretch, helping contain the foot) but also a style statement: Michael had mentioned he wanted a shoe he could wear with a suitgq.com. Hatfield delivered a sneaker elegant enough for MJ’s tailored look, and the AJ11 debuted to such fanfare that it even made it into Jordan’s comeback playoff games. It was the first basketball shoe to incorporate a carbon fiber plate for support, and its iconic black-and-white patent leather design truly “zigged while others zagged,” as Hatfield put itgq.com. Years later Hatfield revealed that he secretly started designing the Jordan XI during Jordan’s brief first retirement from basketball, correctly betting that MJ would return (which he did in 1995)gq.com. That kind of foresight and confidence endeared him to Jordan. As Michael himself has said, “Tinker is a mad scientist”sneakerfreaker.com – a designer who was always one step ahead.

Over the next several years, Tinker Hatfield and Michael Jordan formed a legendary designer-athlete duo. Hatfield went on to design Air Jordans III through XV (3 through 15) in continuous collaboration with MJen.wikipedia.org, as well as later models like the 20, XX3, XXV (2010), and XX9en.wikipedia.org. Each year’s model pushed new boundaries in technology and style, often drawing from some aspect of Jordan’s life or persona. Hatfield’s design choices and inspirations for the Air Jordan line became the stuff of sneaker lore. For example, the Air Jordan V (1990) sported jagged “flames” on the midsole – Hatfield took inspiration from the nose art of World War II fighter planes, thinking it suited Jordan’s aggressive, high-flying playing stylegq.comsneakerfreaker.com. He even tweaked the motif: traditionally flames on aircraft are painted trailing backward, but Hatfield pointed them forward on the Jordan V to symbolize always moving aheadgq.com. The Air Jordan VI (1991), in which Jordan won his first NBA championship, had a heel tab that was inspired by the rear spoiler of Michael’s sports car, adding a sleek automotive vibe to the shoe. When designing the Air Jordan XI (1995) – which many fans consider one of the greatest Jordans – Hatfield broke with convention by adding glossy patent leather to a basketball shoe. This was partly a functional decision (the patent leather doesn’t stretch, helping contain the foot) but also a style statement: Michael had mentioned he wanted a shoe he could wear with a suitgq.com. Hatfield delivered a sneaker elegant enough for MJ’s tailored look, and the AJ11 debuted to such fanfare that it even made it into Jordan’s comeback playoff games. It was the first basketball shoe to incorporate a carbon fiber plate for support, and its iconic black-and-white patent leather design truly “zigged while others zagged,” as Hatfield put itgq.com. Years later Hatfield revealed that he secretly started designing the Jordan XI during Jordan’s brief first retirement from basketball, correctly betting that MJ would return (which he did in 1995)gq.com. That kind of foresight and confidence endeared him to Jordan. As Michael himself has said, “Tinker is a mad scientist”sneakerfreaker.com – a designer who was always one step ahead.

By the late ’90s, Hatfield was finding inspiration even in Jordan’s nicknames and hobbies. The Air Jordan XIII (1998), for example, features a sole patterned after a paw and a holographic “cat’s eye” – a direct nod to Jordan’s stealthy “Black Cat” alter ego on courtgq.com. Remarkably, Hatfield drew that connection on his own; when he presented the “black cat” concept to Jordan, Michael was stunned, telling Tinker that “Black Cat” was what his close friends actually called him – a coincidence that speaks to Hatfield’s almost intuitive understanding of his musegq.com. Throughout the Jordan line, Hatfield consistently blended storytelling with performance: each model had to top the last in innovation, yet also carry a narrative element that fans could latch onto. Whether it was a Ferrari-inspired silhouette for the Air Jordan XIV (reflecting MJ’s love of luxury cars)sneakerfreaker.com or laser-etched graphics of Michael’s life on the XX (2005), Hatfield ensured that every shoe told a story while meeting the high functional demands of a superstar athlete.

It’s worth noting that Hatfield didn’t just design for Jordan’s feet – he also occasionally ventured into designing for Jordan’s head. In the early ’90s Hatfield worked on a collection called Jordan Beyond, attempting to extend the Jumpman magic into apparel and off-court shoes. One sample he created was a dressier basketball shoe perforated like a wingtip oxford, and Michael Jordan even wore a prototype quilted jacket from the line on Saturday Night Live in 1991gq.com. The sub-brand never took off at the time (Hatfield keeps those samples in his archive), but it shows how he was always exploring new ideas for the Jordan brand beyond just sneakersgq.com. This forward-thinking approach later paid dividends as the Jordan Brand eventually did expand successfully into lifestyle shoes and apparel – a vision Hatfield had early on.

Design Philosophy: Form, Function, and Storytelling

What sets Tinker Hatfield apart in the design world is not just the list of hit sneakers he created, but how he creates – his design philosophy. Hatfield approaches footwear design much like an architect or an engineer solving a puzzle, but with an artist’s flair for storytelling. He has stated that every time he sits down to draw, the result is “a culmination of everything that I have seen, done and experienced in life before that point”blog.laced.com. In practice, Hatfield often layers multiple inspirations into a single shoe design. He once explained that he likes to have “three narratives or layers to each design”sneakerfreaker.com. The first layer is pure function: understanding the athlete’s performance needs and solving a problem (a principle he learned from Bowerman). The second layer is personal: reflecting something of the athlete’s personality, interests, or life story. The third layer can be an external inspiration – something seemingly unrelated that sparks a creative idea, like a piece of architecture, a car, or a piece of artsneakerfreaker.com. By combining these elements, Hatfield infuses designs with both purpose and personality. As he says, a basic design might only solve the function, “but a great one will always say something”sneakerfreaker.com. This philosophy is evident in many of his most famous creations.

Notable Examples of Hatfield’s Design Inspirations: Hatfield’s ability to draw from diverse sources has given us some legendary sneaker backstories. Here are a few highlights:

- Nike Air Safari (1987): While working on a new running shoe, Hatfield was inspired by a luxury ostrich-leather couch he saw in a high-end furniture store in New York. He translated that upscale, textured look into the shoe’s spotted “Safari” print on the leather uppersneakerfreaker.com. The idea was to bring an unexpected element of fashion into a running shoe, and it introduced an entirely new print design into the sneaker world.

- Nike Air Huarache (1991): The concept for the Huarache came from water skiing. Hatfield, an avid watersports fan, noticed the snug neoprene booties used in water ski bindings. He applied the neoprene inner sleeve to a running shoe to create the Huarache’s hallmark sock-like fitsneakerfreaker.com. The shoe’s slogan “Have you hugged your foot today?” captured how radical this foot-hugging design felt at the time. It was a gamble – early on even some at Nike doubted the weird-looking Huarache – but Nike exec Sandy Bodecker championed it as the “sneaker of the gods,” and when 5,000 pairs were given to marathon runners, they loved itsneakerfreaker.comsneakerfreaker.com. The Huarache validated Hatfield’s risk-taking approach, proving that sometimes an outlandish idea can redefine comfort and become a cult classic.

- Nike Air MAG (1989/2011): When Hollywood came calling, Hatfield’s futurist side shone. He was asked to design a shoe for Back to the Future Part II that would represent 2015. Rather than simply making a wild fantasy prop, Hatfield wanted a plausible innovation that would excite people about the futuresneakerfreaker.com. He dreamed up self-lacing shoes – the Nike “MAG” worn by Marty McFly in the 1989 film. The movie version used special effects for the auto-lacing, but Hatfield spent the next decades researching how to make it real. This culminated in the Nike HyperAdapt 1.0 in 2016, featuring E.A.R.L. (Electro Adaptive Reactive Lacing) technology that automatically adjusts to the wearer’s footsneakerfreaker.comsneakerfreaker.com. It was a long-term pet project of Hatfield’s to solve an issue athletes face (shoe tightness over time) in a futuristic way. The HyperAdapt and the limited-edition real Nike MAG (finally released with power laces in 2016) showed Hatfield’s commitment to pushing innovation to the edge of imagination.

These examples barely scratch the surface of Hatfield’s prolific output, but they illustrate how his design choices were often fueled by unique inspirations. Whether it was something as grand as a Parisian building or as mundane as a gym bag full of shoes, Hatfield could find a spark of an idea and translate it into sneaker design language.

Legacy and Influence on Sneaker Culture

Tinker Hatfield’s impact on Nike and sneaker culture at large is immeasurable. By the 1990s, he was Nike’s Vice President of Design and Special Projects, heading the famed “Innovation Kitchen” design lab at Nike’s campusen.wikipedia.org. In this role he not only continued to create new products, but also mentored the next generation of designers and set the creative vision for the companydesign.uoregon.edu. Many of Nike’s signature design elements – from the visible Air unit, to hybrid cross-trainers, to neoprene-fit running shoes, to self-lacing tech – trace back to Hatfield’s innovations. He introduced a mindset of bold experimentation that has become part of Nike’s DNA. As curator Ligaya Salazar noted when studying sneaker history, Hatfield’s “willingness to experiment with newly developed technologies [and] references outside of the sneaker world” resulted in unique models that broadened the scope of sneaker designblog.laced.com. Not every wild idea was a home run, of course, but Hatfield’s successes changed the industry’s trajectory. His work helped blur the lines between athletic performance footwear and lifestyle fashion – after Hatfield, sneakers became as much a cultural statement as sports equipment.

The sneakerhead community in particular celebrates Hatfield as perhaps the greatest sneaker designer of all time. Industry publications and fellow designers often use terms like legend, icon, and even GOAT (Greatest of All Time) to describe himsneakerfreaker.com. In 1998, Fortune magazine named Tinker Hatfield one of the 100 most influential designers of the 20th century (across all fields)design.uoregon.edu – a rare honor for a footwear designer and evidence of his reach beyond just sneakers. He has won numerous awards, such as the International Design Award in 1993 for the Nike Huarachedesign.uoregon.edu. Some of his original sketches and Nike prototypes have even made it into design exhibits and the Smithsonian Institution, solidifying his place in design historydesign.uoregon.edu.

Perhaps even more telling is the loyalty and admiration he’s earned from the athletes and collaborators he’s worked with. Michael Jordan’s trust in Hatfield turned into a lifelong partnership – even after Jordan retired from playing, he continued working with Hatfield on the Jordan brand’s designs. Other top athletes like Andre Agassi, Roger Federer, Pete Sampras, and Serena Williams have worn gear designed or influenced by Hatfielddesign.uoregon.edu, and he’s been instrumental in special projects for sports ranging from Olympic track spikes (he crafted golden spikes for sprinter Michael Johnson) to college football uniformsdesign.uoregon.edudesign.uoregon.edu. Hatfield approaches each project with the same ethos: collaborate with the athlete, understand their story, and then create something amazing that performs and inspires. His collaborative style – treating athletes like partners in design – actually helped transform how the industry as a whole develops signature products. Today it’s common for athletes to be heavily involved in the design of their shoes, a practice Hatfield pioneered with Michael Jordan in the ’80ssneakerfreaker.comsneakerfreaker.com.

Even outside of footwear, Hatfield’s creative fingerprints are found in various corners of Nike’s world. He has dabbled in graphic design (designing a basketball court surface for the University of Oregon’s Matthew Knight Arena in 2010en.wikipedia.org, which features a unique tree-ring pattern), in automotive concepts (designing concept car collaborations for video gamesen.wikipedia.org), and more. Yet, he remains most famous for the sneakers. As of today, Hatfield continues to serve in a high-level role at Nike, contributing to special projects and long-term innovation strategydesign.uoregon.edu. He often says he’s focused on “building the Nike of the future”design.uoregon.edu – a fitting mission for someone whose designs have always seemed a step ahead of their time.

In the pantheon of sneaker culture, Tinker Hatfield is a hero figure – the architect who sketched out the shoes that defined eras. The Air Max 1 started a revolution in running shoes; the Air Jordan III through XIV defined the stylistic and performance bar for basketball shoes; the cross-trainers opened new possibilities for athletes; the Huarache showed that comfort and style could co-exist in radical new forms. Sneakerheads revere his designs, retro collectors hunt down his original creations, and new generations of Nike consumers still clamor for products with Hatfield’s imprint. The fact that Air Jordans and Air Maxes from 30+ years ago remain in demand today – often reissued in “retro” releases that sell out instantly – speaks to the timelessness of Hatfield’s work. As Hatfield himself has humbly noted, it’s not just him – it was Nike’s marketing, the rise of hip-hop culture embracing sneakers, and of course Michael Jordan’s global fame that all contributed to the phenomenonblog.laced.com. He insists no single person created Nike’s successblog.laced.com. But without Tinker Hatfield at the drawing board, sneaker history would likely have played out very differently.

Ultimately, Hatfield’s legacy is one of innovation through intuition and daring. He showed that sneaker design could draw from anywhere – from science fiction to sports cars – and that a shoe could capture imaginations as much as it supports feet. He balanced the technical demands of athletic footwear with an artist’s eye for cultural relevance, making sneakers that perform on the court and tell a story on the street. For his contributions, Hatfield has earned a place not just in Nike lore, but in pop culture. As Michael Jordan once quipped in admiration, “Tinker is a mad scientist”sneakerfreaker.com – and for sneaker lovers, that madness has truly been genius.